He Chose Me; I Chose Zion

Sarah’s husband warned her that if she went to see her parents off, he’d push her into the ocean – he never mentioned what he’d do if she boarded the ship with their newborn baby, and set sail for America without him. To Sarah, it was worth the risk.

Sarah Francis Keep lay hidden in the berth of a young couple; her baby’s cries echoed from the other side of the boat as she silently prayed not to be found. The boat sat at port in England, creaking and shifting under the weight of passengers dreaming of the promises which awaited them on the other side of the sea. AMERICAN CONGRESS written boldly on its side.

16 years earlier, in 1849, the Elders broke the ice and baptized Sarah into The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. “Curley Keep, the Latter-day devil, to let a little girl like that be dipped,” the mob called after them as Sarah walked the one and one-half miles home in wet clothes, tucked under her mother’s cloak to shield her from their hateful cries.

Music and light had filled Sarah’s childhood, easing the brassy harshness of hardship and persecution. Soon after joining the Church, however, her family lost everything — their home and five other homes they owned. They were forced to pay rent and came to understand what it meant to live in the depths of poverty. But this did not stop Sarah from singing as she traveled around England with her father and his companion. While Sarah’s angelic voice drew the people near, their teachings drew their souls unto God.

At 18, an extremely devout Sarah dreamed of high mountains and plains, heavenly music and singing. Overwhelmed by the desire to seek out this heaven on earth, she related her dream to the American Elders who confirmed: it was the route to Zion.

When Sarah married against her parents’ wishes, her dreams of Zion became nearly unattainable. Her husband had deceived her, joining the LDS Church solely for her hand. After a month of being married he made it clear she would not be allowed to go to the valley.

On the ship, Sarah continued to to plead with God: that her husband might not find her, that she might make the voyage across the sea, that she might reach Zion. Silence fell over the passengers as the authoritative footsteps of police officers paced about the berths. In gruff voices the names of those to be dragged off the ship were announced, Sarah’s own name listed among them. She sunk deeper into the feathered mattress. Two patent leather shoes caught the dim light, and walked slowly by her hiding place; she forced her eyes tightly shut in prayer.

And her prayer was answered; the shoes passed her by.

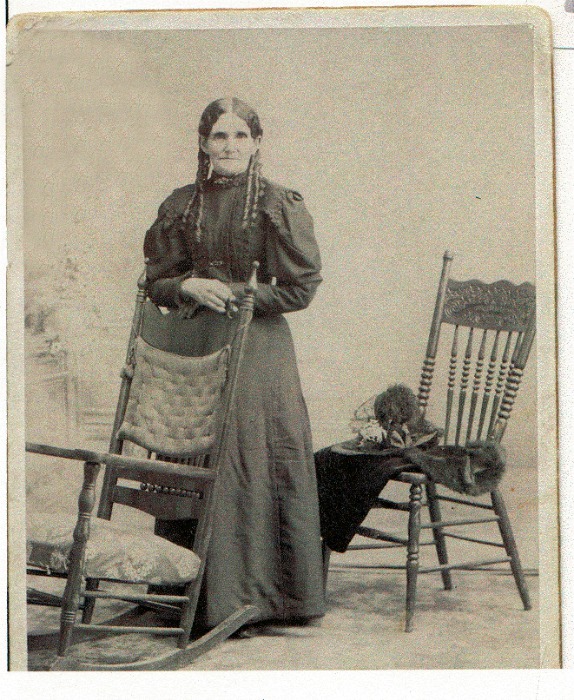

My Great Great Great Grandmother, Sarah Francis Keep (later, Buttars), landed in America, fittingly, on the 4th of July. In the harbor, she watched the fireworks light up the sky with beauty, and even set fire to a ship. There, the tone was set for her travels ahead: her journey to Zion was marked in equal part by perils and blessings.

The Journey to Zion

The wheels of the train caught fire and the passengers were herded into another car “as if [they] were sheep.” Cholera broke out, costing Abner Lowry’s company 71 lives. They buried their dead in quilts and blankets, digging as deep into the sand as they could. Miraculously, neither Sarah nor her baby fell ill.

The wolves howled at night, and perhaps dug up the dead that were buried.

One warm summer night, their camp was visited by 25 or 30 Indians. They stood tall, imposing figures illuminated by the light of the campfire. The scalps of women hung from long hair on their tomahawks, arrows filled their belts, and in their hands they gripped bows.

It frightened us very much, for we were afraid we would be killed.

But after supper and a night of singing, the Indians were pleased and spared their lives.

As the Company made their way to the valley, Sarah was moved by the compassion of those around her. Often times, the Captain would scoop the baby from Sarah’s arms onto his lap, instructing her to walk on. Teamsters would sit on the tongue, pulling Sarah into their wagons to spare her feet. She nursed her baby on small pieces of bacon and baked her bread in the teamsters’ skillets once they were done. Through it all, Sarah sang, not once thinking about the man she left behind.

At last, the Company arrived in Salt Lake City on the 6th of October, 1866 – just in time for General Conference. But Sarah’s journey was not over yet.

Climbing Mountains, Fighting Grasshoppers, and Settling Down

Shortly after arriving in Salt Lake, afflicted with a “cold in her eyes,” Sarah was taken into the care of her sister in Lehi.

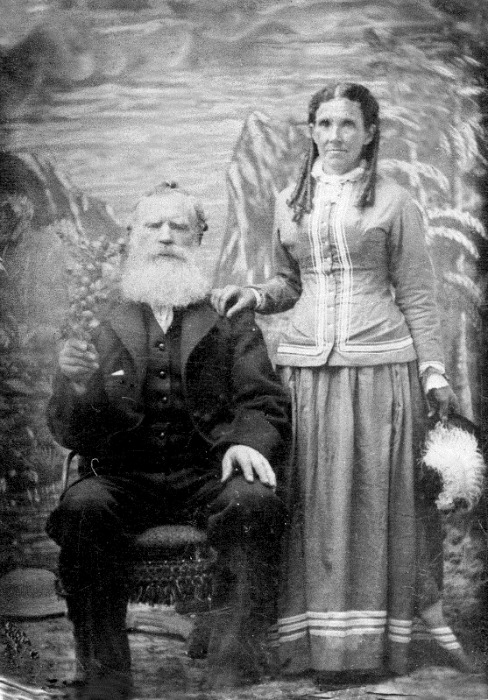

Brother David Buttars was there on business and told me he knew what would cure my eyes, if I would do it. He told me it was Brother Brigham Young’s remedy. I was to dig down a little over a foot deep in the soil, mold the soil, and lay it on my eyes at night in a fine cloth. I did it, and it healed my eyes in a week.

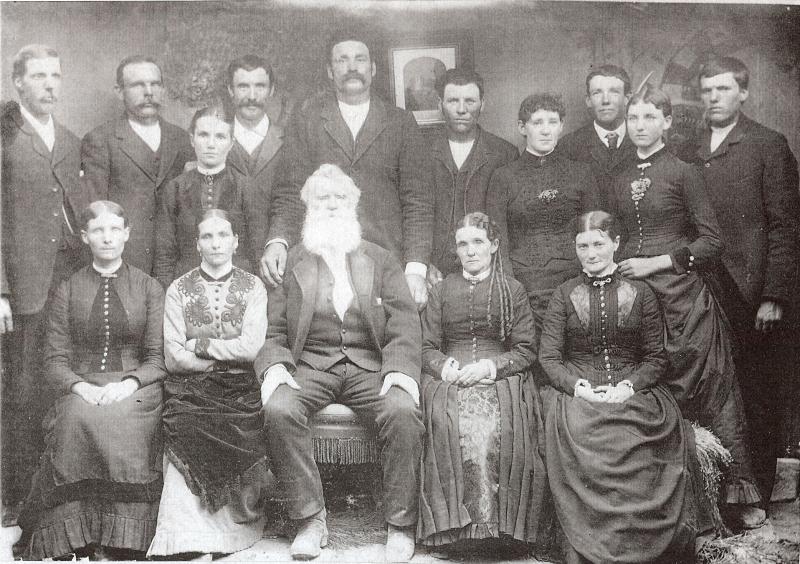

In exchange for sharing the cure, Brother Buttars requested Sarah’s hand in marriage, and she obliged. Sarah, already a mother of one, was now mother to six with the addition of David’s five children. The family set its sight on a home over the mountain, in Clarkston, Cache County, Utah.

As the family was crossing the mountain top, disaster struck. The tongue of their wagon broke and for five days, their horses and cattle were lost. To make matters worse, their broken-down wagon nearly caused a mail coach, manned by President John Taylor, to topple down the mountain. With repairs made, cattle rounded up, and horses tethered, the family started again for Clarkston, arriving in October of 1868.

A small farming town, Clarkston was meant to provide their family with fields of grain to be harvested and sold. However, the Lord had other plans in store for the Buttars.

That fall the grasshoppers were so bad we cut up a cow skin to make a rope, which three of us dragged up and down the garden in order to make the grasshoppers fly away, and to keep them from eating the grain. There were so many grasshoppers, that when they were flying they would darken the sun.

They spent three years fighting off the grasshoppers, using this method, until June 23, 1871, when clouds of seagulls descended upon the town and devoured the vermin. With the grasshoppers gone, the Buttars family was finally able to ease into their life in Clarkston.

Sarah became so deeply invested in the community that people often referred to her as “Grandma Buttars.” She was the first milliner in the town, weaving straw hats, straw braids, and straw trimmings for the hats. She joined the female society in 1869, and held the first “Prayer Circle” in Clarkston at her home for three years until it was moved to the new Tithing Office.

I am thankful that I am here, and have learned what I came here for. I can say the Lord has been with me and given me more than I deserve, but he promised – ‘he that leaves father, mother, husband, wife for the gospel, shall receive a hundred-fold.’ I can see where there was work for me to do here, and the Lord has blessed and preserved my life many times to do this work. I am thankful to him for it.

Sarah died in October of 1935, at the age of 95. A few months before her death she was honored as the oldest pioneer in Cache County. Today, she rests in Clarkston Cemetery, alongside her progeny – my ancestors.