When Can the Government Force You to Sin?

This December, the US Supreme Court will hear a case of a Christian baker who refused to make a same-sex wedding cake. The state of Colorado ordered him to undergo re-education training and start providing cakes for same-sex weddings.

The case, Masterpiece Cakeshop, Ltd v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission, while very complicated, may prove to be one of the most influential in the day-to-day lives of religious believers for a generation.

This article is part one in a five-part series. The series examines many claims made about the case, and the relevant legal precedents and questions.

- “Non-Discrimination is the law, so you have to follow it” or when can the government infringe on your rights?

- “Religious people aren’t exempt from the law” or what are the limits of freedom of religion?

- “Baking a cake is just like selling someone a hamburger” or is baking a cake covered by freedom of speech?

- “If you open a business, you have to serve everyone” or when can business owners legally discriminate?

- “If the baker wins, anyone will be able to discriminate against gays anywhere,” or what are the long-term implications of this case?

I hope to help you understand the many threads of the case, develop your own opinion on the case, and explain your position more clearly to others. This article discusses when the government can infringe on your rights.

What Happened?

In 1993, Jack Phillips opened Masterpiece Cakeshop. He has always run his bakery based on his Christian values. He declines to bake cakes for Halloween, divorces, or with alcohol but serves all people.

In 2012, David Mullins and Charlie Craig went into Masterpiece Cakeshop. They asked Phillips to make them a custom wedding cake. Phillips declined because he does not bake same-sex wedding cakes, but offered to sell them any of his off-the-shelf baked goods.

Mullins and Craig quickly got a rainbow-themed wedding cake made for them at another bakery, then sued Phillips for violating the Colorado Civil Rights Act, which prohibits discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. The case will be argued before the Supreme Court on December 5, 2017.

“Non-Discrimination is the Law, So You Have to Follow It.”

Many people who believe Phillips should have baked the cake, rely on the simple and obviously true logic that you can’t break the law without consequences.

A future article will examine whether or not Phillips, in fact, discriminated on the basis of sexual orientation.

This article focuses on whether the government can force someone to obey the law simply because it is the law? The answer: almost always, but with very important exceptions.

All Laws are Subject to the Constitution

A law that violates the Constitution is not a valid law. For example, even though many states had laws against burning the American flag, the Supreme Court found those laws violated the freedom of speech, so they couldn’t be enforced.

Phillips argues that Colorado’s non-discrimination ordinance violates the “free exercise of religion” and the “freedom of speech” clauses of the Constitution. If the Supreme Court agrees, then Colorado cannot force him to obey that law.

Those who say “non-discrimination is the law, so Phillips must obey,” may think they’re arguing for why he should lose the case, but really they’re only describing the consequence if he loses.

The Government Needs a Very Good Reason to Limit Your Rights

Most rights aren’t unlimited. You can pass a law prohibiting a religion from practicing human sacrifice or using your free speech to conspire to commit a murder, for example.

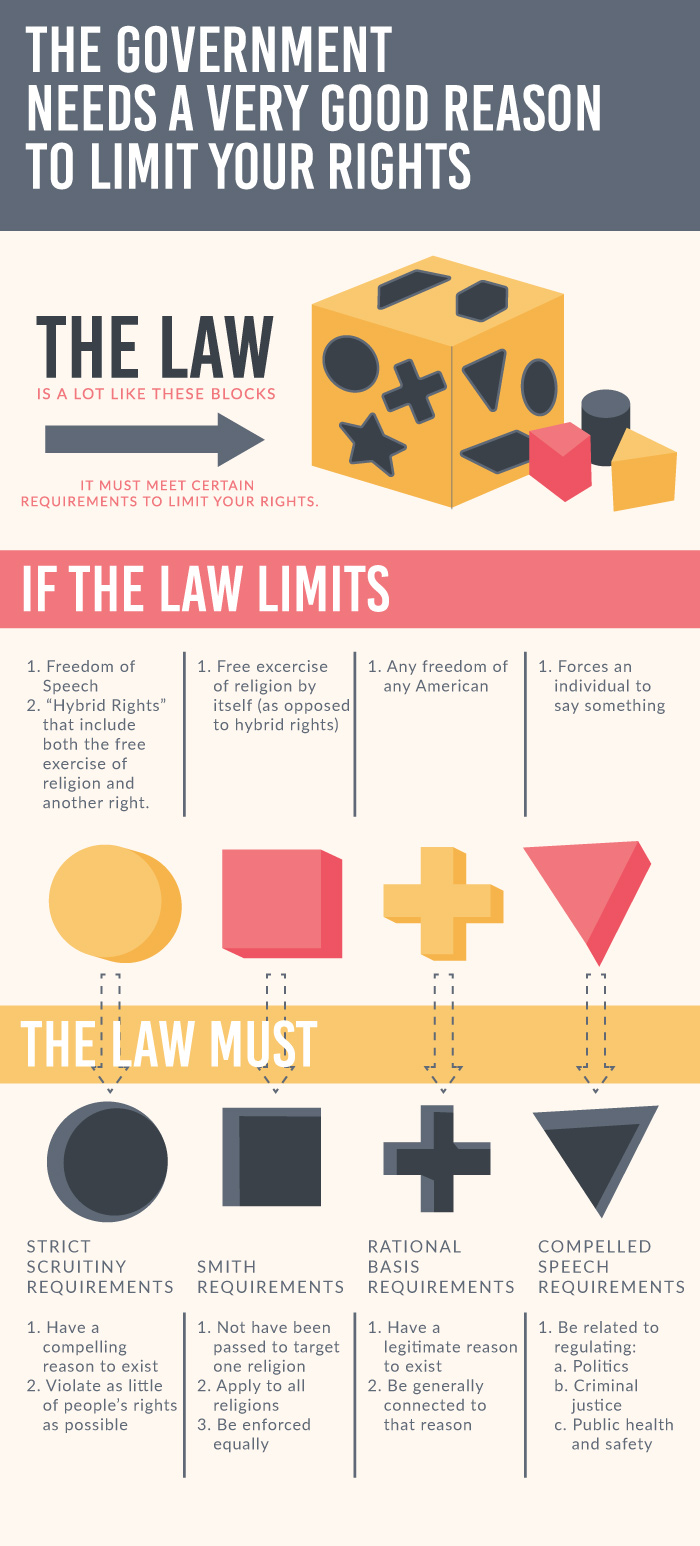

A law, however, must meet certain requirements in order to limit your rights. Different requirements apply depending on context and which right is being limited.

One of the most important questions the Supreme Court will decide is which requirements the law needs to meet in this case. Here are the requirements that may come into play in this case:

Strict Scrutiny Requirements

If a law limits:

- Freedom of speech

- “Hybrid Rights” that include both the free exercise of religion and another right.

That law must:

- Have a compelling reason to exist

- Violate as little of people’s rights as possible

Smith Requirements

If a law limits:

- Free exercise of religion by itself (as opposed to hybrid rights)

That law must:

- Not have been passed to target one religion

- Be enforced equally

Rational Basis Requirements

If a law limits:

- Any freedom of any American

That law must:

- Have a legitimate reason to exist

- Be generally connected to that reason

Compelled Speech Requirements

If a law:

- Forces an individual to say something

That law must:

- Be related to regulating:

- Politics

- Criminal justice

- Public health and safety

In every case, the government must have a reason for a law, but there is a big legal difference between a compelling reason and simply a legitimate reason. This is why the requirements the Supreme Court believes apply in this case will have a big effect on who wins.

In future articles, I’ll examine why the compelled speech and strict scrutiny requirements should apply.

Is There A Rational Basis for Colorado’s Law?

Under even the lowest requirements, however, a law must not just have a general reason, such as non-discrimination, but must have a specific reason for that particular case.

Some argue Colorado’s interest is in preventing discrimination. But what does preventing discrimination accomplish? Here are a couple possibilities.

Could Colorado argue that they have a legitimate government interest in helping Craig and Mullins get a cake? Perhaps, but they got one quickly and without incident.

Could Colorado argue they have a legitimate interest in protecting Craig and Mullins from getting humiliated while shopping? Not really. The Supreme Court has regularly found that avoiding offense is not a legitimate government interest.

So while the requirements used for the case is important, it’s quite possible that the baker could win regardless of the standard chosen.

But What About Civil Rights?

Many people looking at this case compare it to civil rights cases in the 1960s. They conclude that if the government could force a business to serve African-Americans, the government can force a business to serve LGBT+ individuals.

Phillips, of course, would serve LGBT+ individuals, but not a same-sex wedding. We’ll discuss that distinction in article four.

But perhaps more importantly, the government needs a very good reason to force people to do things. The breadth and persistence of racial discrimination lingering from the legacy of slavery is one of the most compelling reasons in history. Relying on the overwhelming power of the federal government should not be replicated often or indiscriminately.

To understand the importance of the government’s cause we must consider the context of 2012 Denver versus 1964 Atlanta.

It is obviously unfair to compare the plight of African-Americans who could not be served for hundreds of miles and a couple who received a free cake at the very next bakery they visited down the street.

But don’t take my word for it, actual civil rights leaders like Dr. Alveda King, Martin Luther King Jr.’s niece, and William Avon Keen, president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference of Virginia, the organization Martin Luther King Jr. started, have come out in support of protecting the baker’s civil rights, and otherwise denying the connection between this case and the civil rights cases of the 1960s.

Besides, the Supreme Court decided in 2015 that the religious beliefs that lead some to oppose same-sex marriage are nowhere near the scourge on society that racism was (and is) when they wrote that the view of marriage as a “union of man and woman” is held “in good faith by reasonable and sincere people.”

Hypothetical

Often in constitutional cases, people will consider hypotheticals that change a few of the facts of the case. Readers can consider how that changes their opinion, and examine why. I’ll include one hypothetical in each article.

Colorado’s civil rights law prohibits discrimination on the basis of creed (i.e. religion). Catholics in the US are a group historically discriminated against. Imagine a Colorado Catholic church has several bakeries from which they order communion wafers, but which have all recently raised their prices.

Another bakery offers custom cookies at a lower price. If that bakery is owned by a Lutheran who opposes Catholic doctrine on communion, can he or she refuse the work? Is the discrimination Catholics faced in this country bad enough to justify the government’s force? Is the fact the Church can otherwise easily obtain communion wafers important? Can the state force the Lutheran to facilitate a Catholic religious ceremony?

Check back tomorrow for our second article that examines whether or not Colorado’s nondiscrimination law violates religious freedom.