People with Different Political Opinions Than You Are Not the Devil

I hate politics.

Or, I guess, to be more accurate, I hate what politics bring out in people.

The amount of name-calling and finger-pointing that occurs across political lines upsets and frustrates me.

We seem to think that because people believe something different than us, they deserve to be hated and verbally trampled upon. They deserve our sneers, snide comments, and eye-rolls. We label others stupid and naive, and sometimes even think that we are better and smarter than they are because their viewpoint is different than our own.

Somewhere along the line, political parties have become deeply derisive to the point where we can’t actually listen to one another’s ideas at all. If someone is conservative but supports gun control measures, they’re a “bad Republican”; if someone is liberal but pro-life, they’re a “bad Democrat.” Rather than supporting ideas and promoting independence of thought, we cling to party lines and when someone’s ideals challenge the norm — or, heaven forbid, our own opinions — we lose our minds.

Part of what makes America such a beautiful place is the ability we have to express our own opinions… But when people do, they’re treated like they’re the devil.

“They Deserve It”

Middlebury College professor and political scientist Allison Stanger wrote an opinion piece for the New York Times in 2017 about her experience at a campus political event that quickly became violent. Stanger is a Democrat, but was looking forward to interviewing the conservative Charles Murray, a scholar at the American Enterprise Institute.

Sadly, instead of a positive experience where both political sides could be represented and listened to, a riot took place. Stanger writes:

“From the stage where I sat with Dr. Murray, waiting for students to take their seats, I saw a sea of humanity. Students were chanting, “Who is the enemy? White supremacy,” and “Racist, sexist, anti-gay: Charles Murray, go away!” Others were yelling obscenities at Dr. Murray or one another. What alarmed me most, however, was what I saw in the eyes of the crowd. Those who wanted the event to take place made eye contact with me. Those intent on disrupting it steadfastly refused to do so. They couldn’t look at me directly, because if they had, they would have seen another human being. . .

Most of the hatred was focused on Dr. Murray, but when I took his right arm to shield him and to make sure we stayed together, the crowd turned on me. Someone pulled my hair, while others were shoving me. I feared for my life. Once we got into the car, protesters climbed on it, hitting the windows and rocking the vehicle whenever we stopped to avoid harming them. I am still wearing a neck brace, and spent a week in a dark room to recover from a concussion caused by the whiplash” (emphasis added).

She goes on to explain that perhaps those students thought they were justified; maybe they thought they were representing people who have been marginalized. Perhaps they thought this man, whom they thought to be a racist, intolerant supremacist DESERVED their hatred. Yet in their rush to label him “intolerant,” they showed a total lack of tolerance and a complete adoption of hypocrisy.

Most upsetting is that the way they handled someone whose opinion they believed to be different than their own is becoming representative of America as a whole.

“But what the events at Middlebury made clear is that, regardless of political persuasion, Americans today are deeply susceptible to a renunciation of reason and celebration of ignorance. They know what they know without reading, discussing or engaging those who might disagree with them. People from both sides of the aisle reject calm logic, eager to embrace the alternative news that supports their prejudices” (emphasis added).

What Stanger said is true; intolerance and an unwillingness to hear another’s opinion is not simply a “liberal” issue — it’s an everyone issue. I’ve heard conservatives call Democrats “snowflakes” more times than I can count. Our own president, a Republican, labels those whom he disagrees with as “dopey,” “crooked,” “irrelevant,” and “dumb” — among a wide stream of other less-than-kind characterizations.

Yes, according to some research, intolerance may be slightly more aggravated among the left — but that doesn’t it mean it isn’t prevalent on both sides of the aisle, because it clearly is. It cannot be dismissed as a “liberal problem,” because it isn’t simply a liberal problem. Regardless of what political party you belong to, intolerance is a huge issue.

Don’t Check Your Religion (or Humanity) at the Door

In 2012, Elder Jeffrey R. Holland gave an incredible devotional entitled “Israel, Israel, God is Calling,” in which he sternly instructed us to never, under any circumstances “check our religion at the door.” To give those who have never heard or read this devotional a little context, Elder Holland discussed a basketball game that took place in Utah where many members of the Church acted horribly, verbally abusing another Saint who had gone to a team outside of the state.

In 2012, Elder Jeffrey R. Holland gave an incredible devotional entitled “Israel, Israel, God is Calling,” in which he sternly instructed us to never, under any circumstances “check our religion at the door.” To give those who have never heard or read this devotional a little context, Elder Holland discussed a basketball game that took place in Utah where many members of the Church acted horribly, verbally abusing another Saint who had gone to a team outside of the state.

“First, let’s finish the basketball incident. The day after that game, when there was some public reckoning and a call to repentance over the incident, one young man said, in effect: ‘Listen. We are talking about basketball here, not Sunday School. If you can’t stand the heat, get out of the kitchen. We pay good money to see these games. We can act the way we want. We check our religion at the door.’

‘We check our religion at the door‘? Lesson number one for the establishment of Zion in the 21st century: You never ‘check your religion at the door.’ Not ever.

My young friends, that kind of discipleship cannot be—it is not discipleship at all. As the prophet Alma has taught the young women of the Church to declare every week in their Young Women theme, we are ‘to stand as witnesses of God at all times and in all things, and in all places that ye may be in,’ not just some of the time, in a few places, or when our team has a big lead.“

I remember hearing that talk and being astounded. How could followers of Christ treat others so terribly? How could they name-call, insult, and disparage another human being so casually?

But how often do we check our own religion — or, for those who aren’t religious, our humanity — at the door? How often do we name-call those who believe differently than us? How often do we label them stupid, idiotic, and foolish? Do we, as Allison Stanger suggested, fail to recognize other people as human beings simply because their opinions (especially their political opinions) differ from our own?

Related: “Intolerance in a ‘Tolerant’ World”

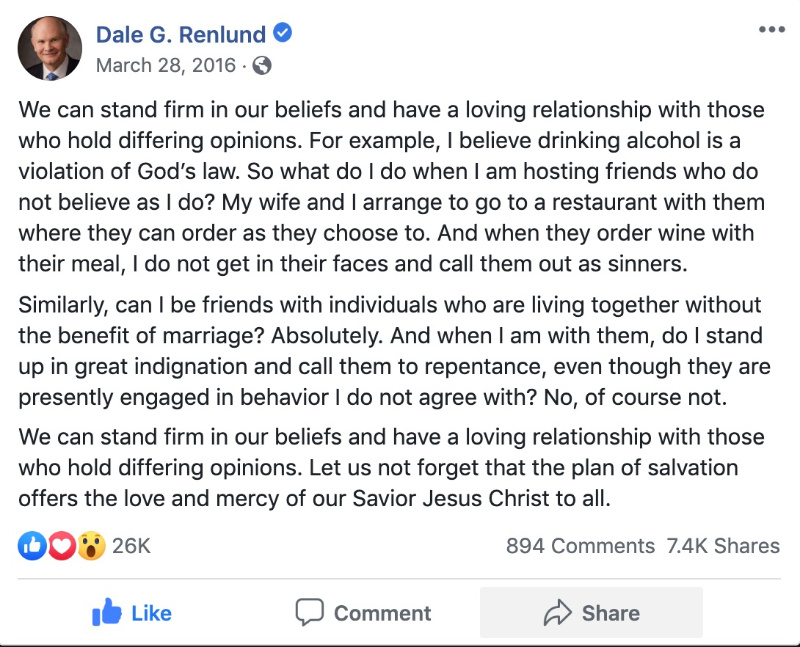

A few weeks ago, I came across a 2016 post from Elder Dale G. Renlund that I think is incredibly important:

We can stand firm in our beliefs and have a loving relationship with those who hold differing opinions. We can disagree and still be civil. We can have different theologies and even political ideologies and still be kind to one another!

Politics and Patience

As I’ve gotten older and more aware of the happenings in the political sphere, I’ve realized that my beliefs don’t align 100% with any one party, candidate, etc. Recognizing this has allowed me to have increased empathy for those on either side of party lines — especially because many of those people may be experiencing the exact same thing.

As I’ve gotten older and more aware of the happenings in the political sphere, I’ve realized that my beliefs don’t align 100% with any one party, candidate, etc. Recognizing this has allowed me to have increased empathy for those on either side of party lines — especially because many of those people may be experiencing the exact same thing.

Instead of focusing so much on our differences when it comes to politics or life in general, I hope we can recognize the things we have in common. Most people — yes, even those who believe differently than you — are just trying to do what they think is right. I have respect for anyone who is striving to stand up for their beliefs because they are genuinely trying to make the world a better place, even if I don’t agree with their ideas.

David Marcus, a reporter for The Federalist, wrote an article I wish every single person in America would read: “We Are Losing The Vital American Value of Tolerance.” In it, he writes:

“People’s increasing unwillingness to engage those with whom they disagree, and the assumption that disagreement implies bad faith, are at best terribly dividing us, and at worst killing us.

. . .

Tolerance is ultimately an expression of humility. We must be humble before he who sees all things because we never will see all things ourselves. Anybody in the United States capable of uttering the phrase ‘Maybe I’m wrong,’ is doing more benefit to the body politic than those who eschew such modesty.

Like all virtues, tolerance comes with dangers that must be considered, lest it turn into relativism. At its worst, tolerance robs us of the ability to make judgments regarding right and wrong. Without an overarching moral framework and, more importantly, laws, tolerance can create chaos. Decent people should not tolerate a good many things. But for the most part political, religious, moral, and philosophical differences do not fall in this category.

It may well be reasonable for those on the left to say they will not tolerate Trump and his supporters’ rhetoric, or for those on the right to say they will not tolerate the chilling of free speech. But what we must remember is that ultimately what is being tolerated is not the idea, but the person espousing it. So long as that person is speaking in a respectful and nonviolent manner, he or she should almost always be extended tolerance.

Take a breath, America. Do not throw your pencil in rage. Use it to describe what you believe, with a trust in the good faith of those with whom you disagree. These are dangerous times. But we can get through them with dispassion and a commitment to tolerance. If we lose that, we lose the American experiment, which is, has been, and will always be the greatest hope of the world. It is in our hands.”

Marcus’s words are imperative in today’s climate. We must remember there are good people on both sides of the aisle, both inside and outside of our Church. I know deeply devoted followers of Christ on either end of the political spectrum — and I believe that’s how it should be. We can and should have different ideas! Most importantly, we should respectfully listen to those who believe differently than we do and engage in civil, thoughtful discussions about why.

I was recently talking to one of my best friends, whom I grew up with on the East Coast. We have always held different political beliefs, but it has never stopped us from being the closest of friends. She said:

“You and I grew up with completely different political ideologies, and even though we differ on some things, we agree on others and we’re still best friends. Now nobody can talk to each other because everyone’s views on things are SO EXTREME.”

Her words reminded me of the wise President Russell M. Nelson’s address at the NAACP convention in July:

“. . . a fundamental doctrine and heartfelt conviction of our religion is that all people are God’s children. We truly believe that we are brothers and sisters—all part of the same divine family.

At that same press conference, President Derrick Johnson and I issued a joint invitation for all people, organizations, and governmental units to work with greater civility, to eliminate prejudice of all kinds, and focus on important interests that we have in common.

Simply stated, we strive to build bridges of cooperation rather than walls of segregation. . .

We are all connected, and we have a God-given responsibility to help make life better for those around us. We don’t have to be alike or look alike to have love for each other. We don’t even have to agree with each other to love each other. If we have any hope of reclaiming the goodwill and sense of humanity for which we yearn, it must begin with each of us, one person at a time.”

Instead of slighting others because of their political leanings and focusing on how different we are, I hope we can, in the words of President Nelson, build “bridges of cooperation rather than walls of segregation.”

No matter our differences, we are all children of God. Each of us has a role in God’s eternal plan. We’re all human beings, so let’s act like it. We need to show compassion, love, and patience to those with whom we disagree.

Let us look at each other through the light of human kindness rather than the shadow of derision, remembering that each and every one of us is of the greatest importance to our Father in Heaven.