Why It Doesn’t Matter if Some Things in the Scriptures Don’t Make Logical Sense

Sometimes we think if something is in the Bible or another holy text, it must have actually happened in real life. This outlook makes it a little difficult to explain things like how Jonah survived living inside a whale for a few days (in case you didn’t know, it’s highly unliekly that it’s scientifically possible to do so) or why there’s a talking donkey in the Book of Numbers (also scientifically unlikely).

So what do we do when the scriptures don’t seem to make any logical sense? Should we just blindly take whatever is in the Bible as a bonafide fact?

I would argue no. A lot of us have made the mistake of assuming that scripture is a genre of its own, which is basically equivalent to calling Netflix a genre. The Bible, like Netflix, is a compilation of various different genres. Jonah and the whale, for example, is a satirical story — it doesn’t make sense scientifically because it was never meant to.

Once we can pinpoint what kind of genre a specific chapter, book, or set of verses it, it becomes a lot clearer what the author’s intended meaning was.

Unfortunately, simply being aware that there are different genres in holy texts isn’t the only tool you need. It’s also helpful to be able to identify different genres so you can understand what’s really going on in the text.

However, this isn’t as easy as it seems. Usually, we are able to identify genres in movies, books and video games because we’re already familiar with the genre options the author or director had to choose from. Unfortunately, the genres from thousands of years ago don’t always match up with our modern ones, so it may be a little difficult for us to identify them without some practice.

In order to get you started on your journey to understanding scriptural genres, I’ve listed a handful of different ones below.

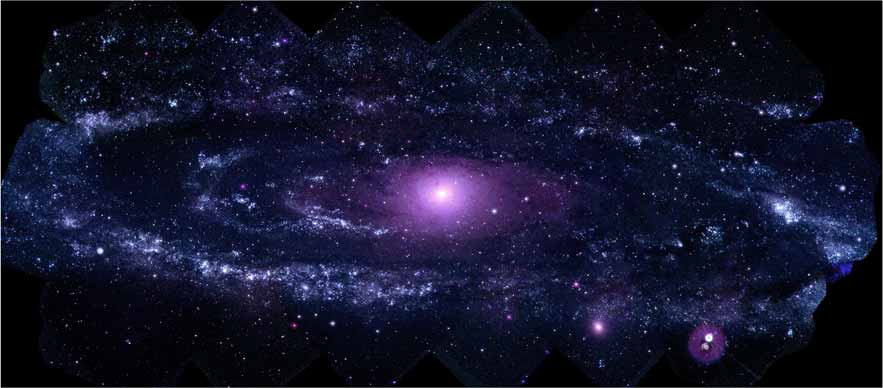

1. Creation/Origin Myths

The word myth here doesn’t mean the story is untrue. The most basic definition of the word myth is simply a traditional story of events that serves to unfold part of the world view of a people or explain a practice, belief or natural phenomenon.

The word myth here doesn’t mean the story is untrue. The most basic definition of the word myth is simply a traditional story of events that serves to unfold part of the world view of a people or explain a practice, belief or natural phenomenon.

Most creation myths feature a state of chaos; the arrival of an organized, all-powerful being; and the creation of the Earth and the heavens by this all-powerful being. Sound familiar?

Now, I’m not saying that the ancient Greek story of Zeus and Genesis are of equal soundness. Nor am I saying everything in Genesis should just be seen as symbolism and legend. From my perspective, God organizing the world is a historically accurate event.

However, I am saying that understanding the purpose and features of a creation myth is extremely helpful. It allows you to see what the author of the text was trying to achieve.

According to Miranda Bruce-Mitford the author of “Signs and Symbols: An Illustrated Guide to Their Origins and Meanings,” “For many, [creation myths] are not a literal account of events, but may be perceived as symbolic of a deeper truth.”

I think a great example of this in Genesis is the description of God taking a rib from Adam to create Eve. It’s always seemed a little odd to me that God just magically removed one of Adam’s ribs.

However, understanding that creation myths often use symbolism helped me understand two things. One, I don’t need to try to figure out scientifically how God was able to safely remove Adam’s rib. Two, I can gain much deeper insights when I’m looking at this symbolically rather than as a historical account.

Now, I’d like to point out that I’m not just pulling these views out of nowhere. In fact, the website of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints says, “The accounts of the Creation in the scriptures are not meant to provide a literal, scientific explanation of the specific processes, time periods, or events involved.”

2. Fables

You probably learned about this one in school, but if you’re like me, you never thought it could apply to the scriptures. In case you need a refresher, a fable is a short story, typically with animals as characters, that conveys a moral.

You probably learned about this one in school, but if you’re like me, you never thought it could apply to the scriptures. In case you need a refresher, a fable is a short story, typically with animals as characters, that conveys a moral.

The story of Balaam and the talking donkey that I mentioned earlier is a prime example of this. In this story, Balaam was making some pretty bad decisions. The Lord sent an angel to stop Balaam, but unfortunately, he couldn’t see the angel. His donkey, however, could, so she tries three different times to avoid going towards the angel with a sword. In response, Balaam beats the donkey, who then responds by asking him what she ever did to deserve such treatment.

If you’re looking at this story thinking it’s a historical account, you’re going to balance that idea with the fact that we know animals don’t talk.

However, if you realize the story is a fable, then it’s clear that the talking donkey is conforming to the features of that genre. You can rest easy knowing you don’t have to find some convoluted way of explaining how the donkey was talking, much in the same way you didn’t bat an eye at Donkey from “Shrek.”

3. Conquest Narratives

We don’t have a modern version of conquest narrative, so it can be difficult to identify when a text is a part of this genre. A conquest narrative is basically a loose retelling of one nation conquering another. Since it’s told from the point of view of the conquerors, it’s likely to include a deal of embellishment as well as some bias.

We don’t have a modern version of conquest narrative, so it can be difficult to identify when a text is a part of this genre. A conquest narrative is basically a loose retelling of one nation conquering another. Since it’s told from the point of view of the conquerors, it’s likely to include a deal of embellishment as well as some bias.

We see this as we look at modern retellings of history, so it shouldn’t be surprising that this was going on thousands of years ago. Being aware that history is never one-sided can allow us to better analyze books like Joshua.

It also can help us account for discrepancies between what historians and archeologists come up with and the Bible. There’s a theory floating around with a lot of archeologists that the events described in Joshua may not have happened exactly as the Bible detailed them. Whether or not that’s true, though, doesn’t really matter since the whole point of a conquest narrative isn’t to give a detailed, historically accurate record; it’s to show that your nation, and by extension your God, is better than all the others. If a little exaggeration is needed to do that, then that’s just part of the genre.

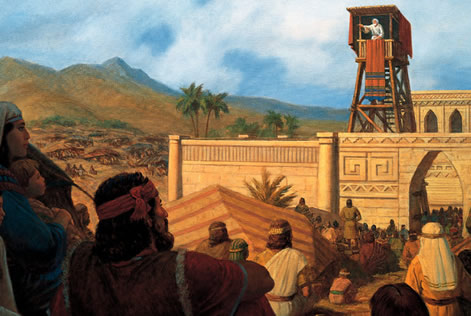

4. Homily

Homily is a fancy word sermon. The purpose of a homily is to spiritually edify the reader rather than to give doctrinal instruction.

Homily is a fancy word sermon. The purpose of a homily is to spiritually edify the reader rather than to give doctrinal instruction.

One of the most well-known homilies in the Book of Mormon is King Benjamin’s speech at the beginning of Mosiah.

An important thing to consider when reading a homily is who the intended audience was. In Abinadi’s sermon to King Noah and his wicked priests, it’s clear that the prophet is specifically directing his comments to nonbelievers. Likewise, when Lehi is teaching at the beginning of 2 Nephi, it’s clear that he’s speaking directly to his sons.

In each of these examples, it’s important that we don’t try to apply things to ourselves that were only meant for the intended audience. I’m not saying we shouldn’t apply the scriptures to ourselves, but I am suggesting that an understanding of a homily’s intended audience can help us choose how to best apply the scriptures to our own lives. It’s usually easier to apply the scriptures to ourselves once we know what the original meaning and context were of a given passage.

In Lehi’s case, for example, we can learn from his example of parenting. Yes, there are bits of wisdom we can pull from his sermons to his sons, but we also know that we don’t have to take phrases like “inasmuch as those whom the Lord God shall bring out of the land of Jerusalem shall keep his commandments, they shall prosper upon the face of this land” (2 Nephi 1:9) don’t mean you have to live in the Americas to get blessings for keeping God’s commandments.

5. Apocalyptic Texts

If Revelation or Daniel seem a little pessimistic, there’s a reason for that — they’re apocalyptic works of literature. Features of this genre include the use of a narrative form and esoteric language. It also insinuates that the end of the world is imminent.

When you understand those features, it makes a lot more sense why the Book of Revelation, which was written thousands of years ago, uses language like “I come quickly” (Revelation 22:7). The author is trying to stress the end of the word and how the positive fate of the righteous in order to prepare people to make changes to prepare to meet their own end, whether that’s at the same time as the Second Coming or not.

I’d like to add that genre certainly isn’t the only thing you should be looking at during your scripture study. Could God do something like make a donkey talk? Since all things through God are possible, maybe. But I’d like to think God works through natural laws.

I think we need to be careful in assuming everything in the Bible is 100 percent factual. In my opinion, some of those stories were never meant to be taken literally, so having a knowledge of scriptural genres is an important tool to have in your scripture study tool belt. When you use that tool, it’s easier not to take the scriptures out of context.