Would Early Mormons Kneel with Kaepernick?

The early members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints suffered numerous acts of violence at the hands of their non-Mormon neighbors. Tarring and feathering, the Hawn’s Mill Massacre, the extermination order issued by the Missouri governor, former U.S. President Martin van Buren declaring to the prophet Joseph Smith, “your cause is just, but I can do nothing for you”—in the face of such hate, it is not surprising that members harbored a great deal of distrust toward the federal and state governments of the time.

Shortly after Joseph and Hyrum Smith’s martyrdom in 1844, all but a few saints abandoned hope of a harmonious existence with their fellow citizens and fled west. However, despite their betrayal by those duty-bound to protect their civil liberties, members of the Church still considered themselves citizens of the United States.

In fact, a Deseret News article claimed that “the ‘Mormon’ people are the most loyal community within the pale of the Republic of the United States of America.” Though the Utah Territory would not become a state until 1896, patriotic Utahns celebrated Independence Day and flew the American flag.

Fast forward to 1885, and Church members’ reprieve from governmental pressure was already coming to an end. Conflict over the continued practice of polygamy kept tensions high. On July 4th of that year, LDS President John Taylor dictated that the flags of all Church establishments, and some public buildings, be flown at half mast. This was meant as an expression of grief—a protest of what members saw as the oppression of their religious liberty. President Taylor also cautioned members not to engage in violence.

Fast forward to 1885, and Church members’ reprieve from governmental pressure was already coming to an end. Conflict over the continued practice of polygamy kept tensions high. On July 4th of that year, LDS President John Taylor dictated that the flags of all Church establishments, and some public buildings, be flown at half mast. This was meant as an expression of grief—a protest of what members saw as the oppression of their religious liberty. President Taylor also cautioned members not to engage in violence.

Nevertheless, those Utahns who were not of the Mormon faith saw this peaceful protest as “the mark of treason.” One Salt Lake Tribune article’s description of their reactions sounds vaguely familiar:

One demonstrator said he was “as mad as when Fort Sumter was fired on.” The Grand Army of the Republic, the Union veterans’ organization, branded it “a deliberate expression of Mormon contempt and defiance of the law which that flag represents.” Even ex-Confederate soldiers proposed holding an “indignation meeting” on the 24th to denounce “the insult offered to the flag on July 4, by the Mormon church.”

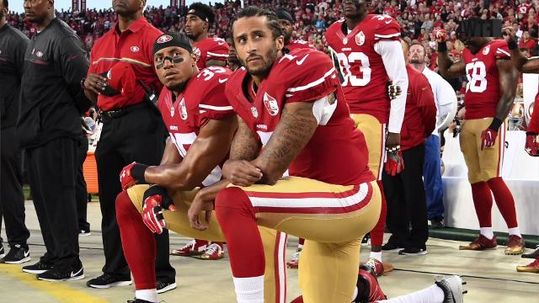

I cannot help but draw a parallel between these accounts and the much-debated “kneeling” by today’s NFL athletes. Without supporting or condemning the cause of either party, one must recognize that both groups took action in an effort to express feelings of injustice, oppression, and a lack of empathy from their government and fellow citizens.

Some might argue that, by lowering the flag, the early Mormons’ protest actually demonstrated even greater disrespect than that shown by a kneeling Kaepernick. I see indignation expressed by people all over the nation, many of them fellow members of the Church, and I wonder—would they have responded similarly to the events of 1885?

The point that seems lost on many is that, regardless of whether you think they should, the right to peacefully protest is one shared by every citizen of this nation. If anything, the backlash against such demonstrations has the effect of fanning the flames rather than helping people to understand one another and reconcile their differences.

Put it this way: if you believe that a person’s reasons for protesting are misguided, misinformed, and misplaced (and tell them so in no uncertain terms), have you gained a friend or made an enemy? How likely is that person to listen to your reasoning? Will you have helped to relieve his concerns, or will your attitude serve only to strengthen his suspicions? Likewise, protesters do themselves no favors when they accuse everyone who disagrees with them of racism, sexism, and -isms ad nauseum.

I am not suggesting that we refrain from saying honestly what we believe, or from standing up for what we know to be right. However, I know from personal experience that debates laced with sarcasm and condescension only drive the wedge deeper. The prophets and apostles have been urging us for some time now to temper our passionate discussions with the respect due to every person as a child of God.

In his address Refuge from the Storm, Elder Patrick Kearon reminds us, “As members of the Church, as a people, we don’t have to look back far in our history to reflect on times when we were refugees, violently driven from homes and farms over and over again. Last weekend in speaking of refugees, Sister Linda Burton asked the women of the Church to consider, ‘What if their story were my story?’ Their story is our story, not that many years ago.”

As members of the Church, are we so far removed from the oppression of our past that we have no empathy left for others who still experience it?

I hear quite often that we need to eradicate hate from our society. Given the horrific and heartbreaking events recently in Las Vegas (and elsewhere), I agree. However, I don’t think that is the real culprit for most of us. I believe that indifference is the worst and most common affliction among us today. It is easy to assure yourself that you don’t hate anyone, because you genuinely try to be a good person, then turn a blind eye to the real hate that occurs around you. Or express annoyance when an athlete kneels in acknowledgment of the racism that many of his—our—brothers and sisters still experience.

My husband once said, “No one will ever listen to you if you aren’t willing to listening to them.” Is there room in our hearts to lay aside our opinions for a moment and lend a listening ear? Are we prepared to consider that, in spite of all we think we know, we might be missing a few things?

Could it be that, if they were here, some of our pioneer forefathers would leave our side and kneel with Kaepernick?